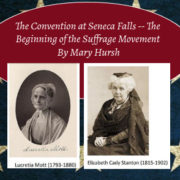

The Convention at Seneca Falls — The Beginning of the Suffrage Movement

The power and the enticement of the right to vote brought over three hundred men and women to the tiny hamlet of Seneca Falls, New York, in the summer of 1848 to attend the first women’s rights convention organized by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, two abolitionists who had met at the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention in London. These women realized early that to achieve reform, women needed to win the right to vote. The idea for the convention began when Mott and Stanton, along with Martha Wright and Mary Ann McClintock, were invited to tea at the home of Jane Clothier Hunt, a wealthy philanthropist and abolitionist, in Waterloo, New York. The ladies talked about the need to improve the social standing of women as well as the need for women to have the right to vote.

Spurred on by the motto of a Hunt grandfather, “ Faith without works is dead,” the women decided to move forward with their cause and send an advertisement to the Seneca County Courier inviting all readers to attend a convention planned at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls where the conditions and rights of women would be the topics of discussion. The chapel, after all, had been the scene for many reform lectures over the years.

Wright, McClintock, Hunt, Stanton, and Mott met supporters on July 19, at the Wesleyan Chapel. The first day of the convention was especially for women who gathered to hear Stanton read the Declaration of Sentiments, Grievances, and Resolutions, listing injustices inflicted on women. The document urged all women to organize and petition for their rights.

Nearly forty men attended the second day of the convention on July 20, including Frederick Douglass. The convention passed twelve resolutions that day including the ninth resolution calling for female enfranchisement.

The document listed sixteen abusive laws and practices that violated women’s natural rights such as withholding rights given to natives and foreigners; withholding the right to vote; withholding the right to own property. The declaration emphasized that rules of marriage, divorce, education, religion and even moral laws were all designed to destroy a woman’s confidence in her own powers. Stanton emphasized that these laws were enacted without the consent of the governed since women were denied the franchise. This convention marked the beginning of the women’s suffrage movement.

The Declaration of Sentiments, Grievances, and Resolutions was modeled on the Declaration of Independence. Stanton’s opening paragraph reads, “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man…we hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal.” The document goes on to refuse allegiance to a tyrannical government and to insist on equal status so women can enjoy their natural rights. Both documents were written to help people live in a more just society. The Declaration of Independence was signed by fifty-six men and the Declaration of Sentiments, Grievances, and Resolutions was signed by sixty-eight women and thirty-two men of a total of three-hundred attendees of the convention. Seventy years after the Declaration of Sentiments, Grievances, and Resolutions was adopted, the l9th Amendment was passed by Congress granting women the right to vote.

This article is the second in a series on the Women’s Suffrage Centennial sponsored by Chautauqua-Wawasee, Syracuse-Wawasee Historical Museum, Syracuse Public Library, Syracuse-Wawasee Chamber and Indiana Humanities. All events are free and open to the public.

Chautauqua-Wawasee is a non-profit organization which provides life enriching programs for the northern Indiana region.

Mary Hursh is a freelance writer who lives on Syracuse Lake with her husband Stanley.